My journey to the river valley of western Minnesota has me thinking about feet.

I didn’t plan to be here. Honestly, the phone interview three months ago had me worried – a PT department completely vacated, patients diverted last minute to neighboring sister clinics. When anthropologists study a civilization that was suddenly abandoned, they suspect plagues or natural disasters; what sort of disaster had prompted this sudden staff exodus?

I exchanged the necessary pleasantries with my interviewer and planned to give my polite “no thanks” after a weekend of deliberation.

But then a niggling Voice started to whisper. “What if this opportunity were listed as a mission project? Would you consider it then? Do you think you could be of service here?”

Dagnabit.

So I landed in a town on a hill beside the river.

Feet are neat. These oft-neglected grounders, serving as anchor points for most of our adult movement, have some of the most fascinating physiology of the musculoskeletal system. With each step, your foot converts magically* from a springy, shock-absorbing cushion into a rigid springboard that propels you toward your object of pleasure – for me, a heavy-laden fruit tree or an expansive overlook vista.

*Ok, it’s not magic, because you can understand it and it’s way cooler.

The bones in your feet make up over 1/4 of all 206 bones in your body. The 26 bones of each(!) foot fit together in a mindbending puzzle that gets floppy when you twist it one way, firm when you twist it the other (pronation and supination for you aspiring anatomy nerds). The interaction of the big toe, midfoot/arch, heel, ankle, knee, and hip work in a dizzying orchestration of twisting and untwisting, unlocking and relocking, flopping and firming – with each step. What a marvelous design!

But sometimes feet hurt. And when feet hurt, you get to show your little piggies to someone like me. I twist those feet, look at those arches, tug on those toes, and try to restore that foot magic. And many times, I turn my ire toward the foot coffins you walked in with: canvas and rubber boxes that bind and squeeze your toes into unnatural points, with cushions that push you off-balance and block your ground-sensing nerves from feeling the earth. Of course, your extremely adaptive body has yielded to years of being strapped into pointy molds, so it takes time to re-nature your feet. Re-naturing can bring its own kind of discomfort.

You probably have some history of foot re-naturing. In my childhood home, dandelions’ cheery faces signaled permission to venture unshod outdoors (even though we were encouraged to scamper shoeless in the snow to show how brave we were). Driveways’ gravel and lawn-nestled twigs always felt sharpest before the dandelions’ hair turned gray, our feet “toughening up” through early spring as we hobbled on fresh textures and sensations. By midsummer, our soles embraced all walks of life without hesitation. We didn’t need shoes to protect us from nature’s varied surfaces; our flexible feet had adapted to accommodate these shapes and edges without signaling distress.

When Moses was in the wilderness tending his father-in-law’s sheep, he was drawn to a supernaturally smoldering shrub and called to “Take off [his] shoes, for [he was] standing on holy ground.”

I like to think I was called to go barefoot in Minnesota this winter.

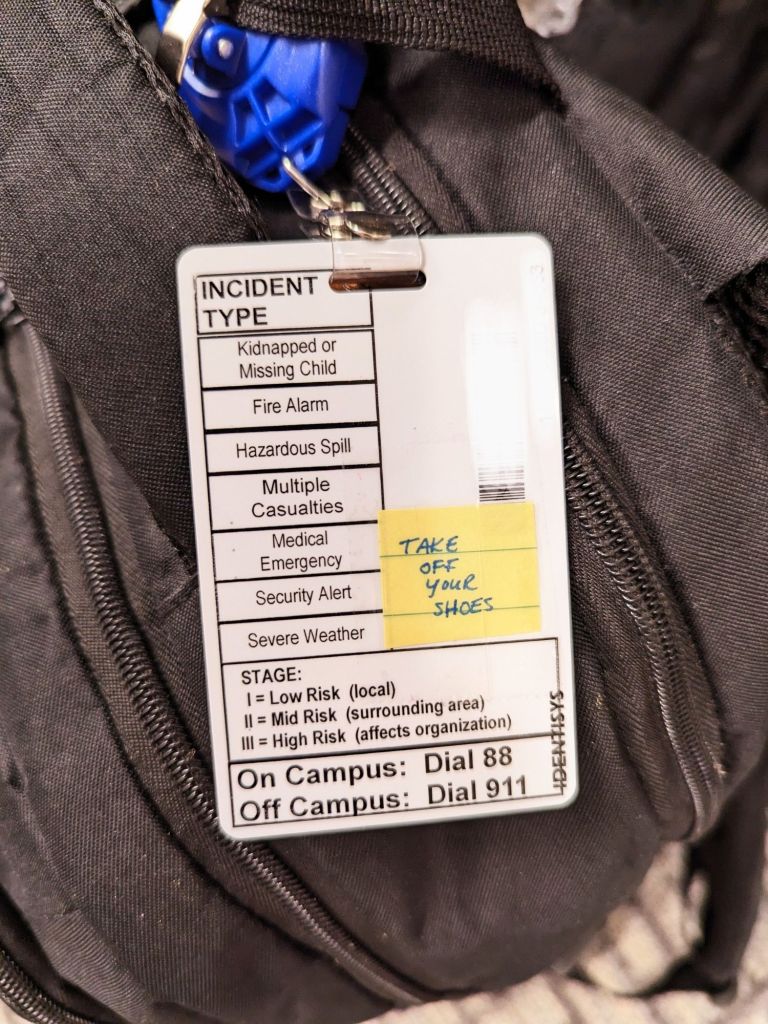

A small reminder is scrawled on the back of my work ID badge: Take off your shoes. This is my reminder that I am on holy ground. When I tend to any patient, I recognize that I am in a place of honor, accepting the great privilege of receiving someone’s trust to help them navigate a time of pain and weakness. I remember that this patient has come to me soul-bare, vulnerably sharing their weaknesses and allowing me to touch the tender spots, trusting me to offer a gentle hand. This is where I meet the God of the wilderness, the untamed God who engulfs bushes in flames and turns sticks into snakes, but who also restores withered hands and calls the lame to walk. Where He is, the ground is sacred.

Modern shoes keep our feet separated and protected from the surface we are walking on, but at the expense of our foot functioning properly as a flexible, sensory organ. Perhaps God wanted Moses – wants me – to be in direct contact with His wild presence.

This will be uncomfortable to start. When I ditch my shoes, I feel everything more keenly. There is less to shield me from the textures of the wild – the pebbles and the sand and the briars. Initially, I’m much more likely to feel discomfort – even pain. But the more I bare my sole to new sensations, the more effectively I adapt to and engage with my environment. I am inherently more present and more grounded.

Take a look at your feet. Aren’t they fascinating? Isn’t it amazing how they carry you, how they twist and pivot to balance and propel you?

But are they functioning as they were designed, as a wonderfully sensitive tool for navigating your world? Do they mirror other areas that could deal with a bit of re-naturing?

Is it, perhaps, time to take off your shoes – to bare your souls?